Why the Supreme Court’s Football Coach Decision is a Game-changer on School Prayer

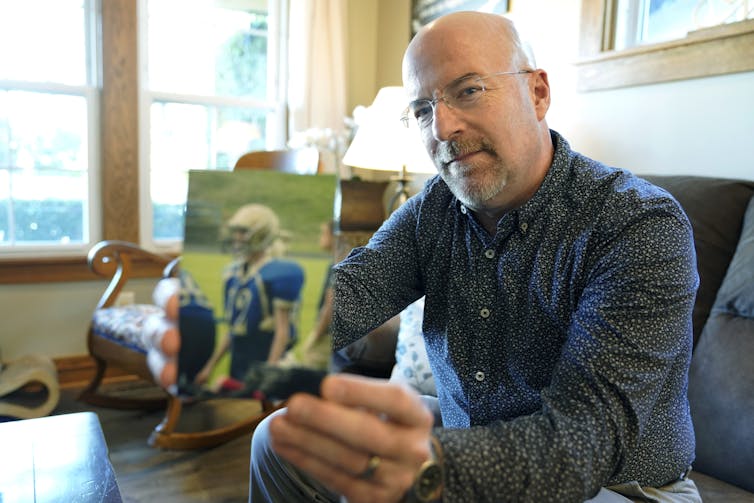

Former Bremerton High School assistant football coach Joe Kennedy answers questions after his legal case, Kennedy vs. Bremerton School District, was argued before the Supreme Court on April 25, 2022 in Washington, DC. Kennedy was terminated from his job by Bremerton public school officials in 2015 after refusing to stop his on-field prayers after football games. Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images

Connecting state and local government leaders

COMMENTARY | The case is noteworthy because the court has now decided that public school employees can pray when supervising students.

The U.S. Supreme Court has consistently banned school-sponsored prayer in public schools. At the same time, lower courts have generally forbidden public school employees from openly praying in the workplace, even if no students are involved.

Yet on June 27, 2022, the Supreme Court effectively gave individual employees’ prayer the thumbs up – potentially ushering in more religious activities in public schools.

In Kennedy v. Bremerton School District – the Supreme Court’s first case directly addressing the question – the court ruled that a school board in Washington state violated a coach’s rights by not renewing his contract after he ignored district officials’ directive to stop kneeling in silent prayer on the field’s 50-yard line after games. He claimed that the board violated his First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and freedom of religion, and the Supreme Court’s majority agreed 6-3.

From my perspective as a specialist in education law, the case is noteworthy because the court has now decided that public school employees can pray when supervising students. It also helps close out a Supreme Court term when the current justices’ increasing interest in claims of religious discrimination was on full display, with another “church-state” case decided in religious plaintiffs’ favor just last week. And on June 24, 2022, the court overturned Roe v. Wade. The debate over abortion is often framed in terms of religion, even though the court’s holding focused on other constitutional grounds.

Facts of the case

In 2008, Kennedy, a self-described Christian, worked as head coach of the junior varsity football team and assistant coach of the varsity team at Bremerton High School. He began to kneel on the 50-yard line after games, regardless of the outcome, offering a brief, quiet prayer of thanks.

While Kennedy first prayed alone, eventually most of the players on his team, and then members of opposing squads, joined in. He later added inspirational speeches, causing some parents and school employees to voice concerns that players would feel compelled to participate.

School officials directed Kennedy to stop praying on the field because they feared that his actions could put the board at risk of violating the First Amendment. The government is prohibited from making laws “respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof” – language known as the establishment clause, which is often understood as meaning public officials cannot promote particular faiths over others.

In September 2015, school officials notified the coach that he could continue delivering his inspirational speeches after games, but they had to remain secular. Although students could pray, he could not. Even so, a month later, Kennedy resumed his on-field prayers. He had publicized his plans to do so and was joined by players, coaches and parents, while reporters watched.

Bremerton’s school board offered Kennedy accommodations to allow him to pray more privately on the field after the stadium emptied out, which he rejected. At the end of October, officials placed him on paid leave for violating their directive and eventually chose not to renew his one-year contract. Kennedy filed suit in August 2016.

Two complicated clauses

Kennedy raised two major claims: that the school board violated his rights to freedom of speech and also to the free practice of his religion. However, the Ninth Circuit twice rejected these claims because it concluded that when he prayed, he did so as a public employee whose actions could have been viewed as having the board’s approval. Moreover, the Ninth Circuit agreed with the school board that the district had a compelling interest to avoid violating the establishment clause.

During oral arguments at the Supreme Court, though, it was clear that the majority of justices were sympathetic to Kennedy’s claims of religious discrimination and more concerned with his rights to religious freedom than the board’s concern about violating the establishment clause.

Writing for the court, Justice Neil Gorsuch noted that “a proper understanding of the Amendment’s Establishment Clause [does not] require the government to single out private religious speech for special disfavor. The Constitution and the best of our traditions counsel mutual respect and tolerance, not censorship and suppression, for religious and nonreligious views alike.”

One aspect of Kennedy with potentially far-reaching consequences is that it largely repudiates the three major tests the court has long applied in cases involving religion.

The first, Lemon v. Kurtzman, was a 1971 dispute about aid to faith-based schools in Pennsylvania. The Supreme Court’s decision required that interactions between the government and religion must pass a three-pronged test in order to avoid violating the establishment clause. First, an action must have a secular legislative purpose. In addition, its principle or primary effect must neither advance nor inhibit religion, and it cannot result in excessive entanglement between the government and religion. Regardless of whether one supported or opposed the “Lemon test,” it was often unwieldy.

A decade later, in Lynch v. Donnelly – a case about a Christmas display on public property in Rhode Island – the court determined that governmental actions cannot appear to endorse a particular religion.

Finally, in 1992’s Lee v. Weisman, a dispute from Rhode Island about graduation prayer, the court wrote that subjecting students to prayer was a form of coercion.

The Supreme Court has backed away from the Lemon test for years. In 1993, Justice Antonin Scalia caustically described it as “some ghoul in a late-night horror movie that repeatedly sits up in its grave and shuffles abroad, after being repeatedly killed and buried, […stalking] our Establishment Clause jurisprudence.”

Kennedy may have put the final nail in Lemon’s coffin, with Gorsuch writing that the court should instead interpret the establishment clause in light of “historical practices and understandings.” He went on to remark that “this Court has long recognized as well that ‘secondary school students are mature enough’” to understand that their schools allowing someone freedom of speech, in order to avoid discrimination, does not mean officials are endorsing that view, let alone forcing students to participate.

Moving forward

In a lengthy dissent almost as long as the opinion of the court, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan, expressed their serious reservations about the outcome. Setting the tone at the outset, Sotomayor chided the court for “paying almost exclusive attention to the Free Exercise Clause’s protection for individual religious exercise while giving short shrift to the Establishment Clause’s prohibition on state establishment of religion.”

The dissent echoed some points from the June 21, 2022, dissent in Carson v. Makin, another high-profile case about religion and schools, where Sotomayor criticized the majority for dismantling “the wall of separation between church and state that the Framers fought to build.”

Kennedy v. Bremerton is unlikely to end disagreements over public employees’ prayer as free speech, or the tension between the free exercise and establishment clauses.

In fact, the case brings to mind the saying to be careful what one wishes for, because one’s wishes may be granted. By leaving the door open to more individual prayer in schools, the court may also open a proverbial can of worms. Will supporters who rallied behind a Christian coach be as open-minded if, or when, other groups whose values differ from their own wish to display their beliefs in public?

Meanwhile, Kennedy has said that he would like his job back – so stay tuned.

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Charles J. Russo, Joseph Panzer Chair in Education in the School of Education and Health Sciences and Research Professor of Law at the University of Dayton.

NEXT STORY: How One City Is Adressing 911 Calls That Require a Mental Health Response