Poverty In 2021 Looks Different Than in 1964 – But the US Hasn’t Changed How it Measures Who’s Poor Since LBJ Began His War

This April 24, 1964, file photo shows President Lyndon Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, center left, leave the home in Inez, Ky., of Tom Fletcher, a father of eight who told Johnson he'd been out of work for nearly two years. (AP Photo/File)

Connecting state and local government leaders

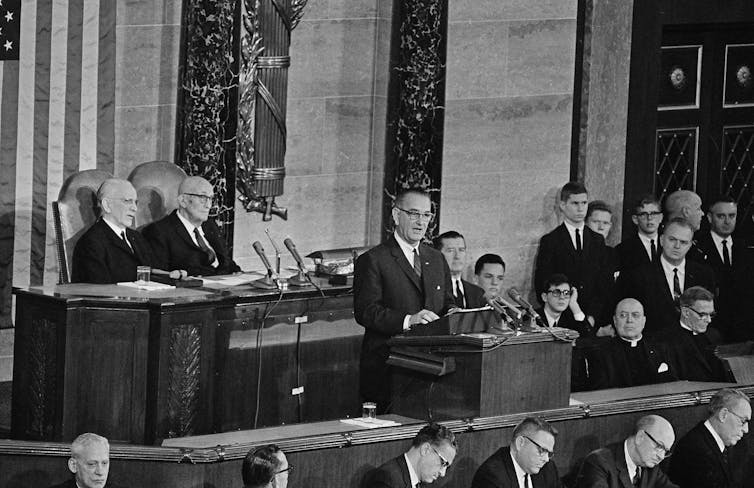

In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson famously declared war on poverty.

“The richest nation on Earth can afford to win it,” he told Congress in his first State of the Union address. “We cannot afford to lose it.”

Yet as the administration was to learn on both the domestic and foreign battlefields, a country marching off to war must have a credible estimate of the enemy’s size and strength. Surprisingly, up until this point, the U.S. had no official measure of poverty and therefore no statistics on its scope, shape or changing nature. The U.S. needed to come up with a way of measuring how many people in America were poor.

As I discuss in my recently published book “Confronting Poverty,” the approach that the government came up with in the 1960s is still – despite its many shortcomings – the government’s official measure of poverty and used to determine eligibility for hundreds of billions of dollars in federal aid.

Counting the poor

Broadly speaking, poverty means not having the money to purchase the basic necessities to maintain a minimally adequate life, such as food, shelter and clothing.

The government came up with its official method for counting poor people in the mid-1960s.

First, it asks, what does it cost to purchase a minimally adequate diet during the year for a particularly sized family? That number is then multiplied by three, and you have arrived at the poverty line. That’s it.

If a family’s income falls above the line it is not considered in poverty, while those below the line are counted as poor.

What about all the other basic necessities, such as housing, clothing and health care? That’s where the multiplier of three comes in. When the poverty thresholds were devised, research indicated that the typical family spent approximately one-third of its income on food and the remaining two-thirds on all other expenses.

Therefore, the logic was that if a minimally adequate diet could be purchased for a particular dollar amount, multiplying that figure by three would give the amount of income needed to purchase the basic necessities for a minimally adequate life.

Back in 1963, that translated into a poverty line of US$3,128 for a family of four. In 2019, the same family’s poverty line stood at $26,172. For an interesting contrast, that’s less than half what the average American polled in 2013 said was the “smallest amount of money” a family of four needed to get by, or $58,000.

The federal government adjusts the poverty line annually to reflect increases in the cost of living. The cutoff itself varies by the number of people in the household, while a household’s annual income is based upon the earnings of everyone currently residing within it.

Using this measure, 10.5% of the U.S. population was in poverty in 2019, the most recent data available.

Keep in mind, though, these thresholds represent impoverishment at its most opulent level. Among those living below the poverty line, 45% live in “deep” poverty, which means they live on less than half of the official poverty line.

The government uses the official poverty line as the base to determine who’s eligible for a range of social programs, from Medicaid to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. For example, to qualify for SNAP, a household must be below 130% of the poverty line for its size.

Other measures of poverty

Most analysts, however, consider the official poverty line to be an extremely conservative measure of economic hardship.

A major reason for this is that families today have to spend much more on things other than food than they did in the 1960s. For example, housing costs have surged over 800% since then.

For that reason, some critics say the multiplier of three should be raised to four or even higher. Taking that step would result in a much larger percentage of the population being seen as in poverty, making them eligible for anti-poverty benefits.

In response, in 2011 the census bureau developed an alternative measure of poverty, called the Supplemental Poverty Measure. This method takes into account a number of factors that the official poverty measure does not, such as differences in cost of living across the country. The result pushes the poverty rate up just a tad, to 11.7% for 2019. This measure is mostly used today by academics and researchers.

Another method, common in many high-income countries, ignores the cost of living calculations entirely.

The European Union, for example, defines poverty as the percentage of the population that earns below one half of whatever the median income is. For example, in the U.S., the median income in 2019 was $68,703, which means anyone earning less than $34,351 would be deemed poor. By that measure, the U.S. would have a poverty rate of 17.8%.

In fact, back in 1959, the poverty line for a family of four was about half of median income in the U.S. Today, it’s about a quarter, which means the federal government’s definition of who is poor hasn’t kept up with overall rising standards of living.

One other approach is based on the idea that poverty is more than just a lack of income and should reflect economic insecurity more broadly, such as not having unemployment or health insurance. The census recently calculated what poverty might look from this perspective and concluded 38% of Americans experienced one or more aspects of deprivation in 2019.

The only way to win the war

Why does it matter how a society measures poverty?

It matters because in order to address a problem, you must have a clear understanding of its scope. By using an extremely conservative measurement such as the federal poverty line, the U.S. minimizes the extent and depth of poverty in the country.

An inaccurate poverty line inevitably also limits the number of impoverished people who qualify for much-needed federal and state assistance. During the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of people would have fallen into poverty were it not for less conditional coronavirus aid from the federal government, such as the three rounds of economic impact checks and supplemental federal employment insurance.

Many Americans in the past have been rudely surprised at just how inadequate America’s safety net is, at least in part because it’s based on outdated federal poverty thresholds. Broadening the definition of poverty would ensure it’s more likely to be there to support people in a crisis.

Ultimately, poverty will touch the majority of Americans at some point in their lives. My own research shows that roughly 6 in 10 Americans will spend at least one of their adult years below the official poverty line.

But if the U.S. ever hopes to finally win the war LBJ began in 1964, the poor need to be seen in order for the government to lift them out of poverty.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Mark Robert Rank is a professor of social welfare at Washington University in St Louis.

NEXT STORY: Two-Thirds of US Adults Believe Life is Returning to Normal