The Geography of Disaster Risk and Resiliency in America: Alaska

StartIn “The Geography of Disaster Risk and Resiliency in America,” a series of Route Fifty dispatches that will be part of a larger forthcoming ebook, I’m featuring locations that provide snapshots of the very real dangers and disruptions that emergency planners, first responders, public officials and other stakeholders face, plus the strategies and technologies helping our communities be more resilient.

I’m starting in Alaska and will be heading into the Pacific Northwest. Since this part of the United States sits on the Pacific “Ring of Fire,” there will be many stories about volcanoes, earthquakes and tsunamis. But it’s also about landslides, flooding, wildfires, nuclear waste, sewage treatment and the continuity of government during a crisis.

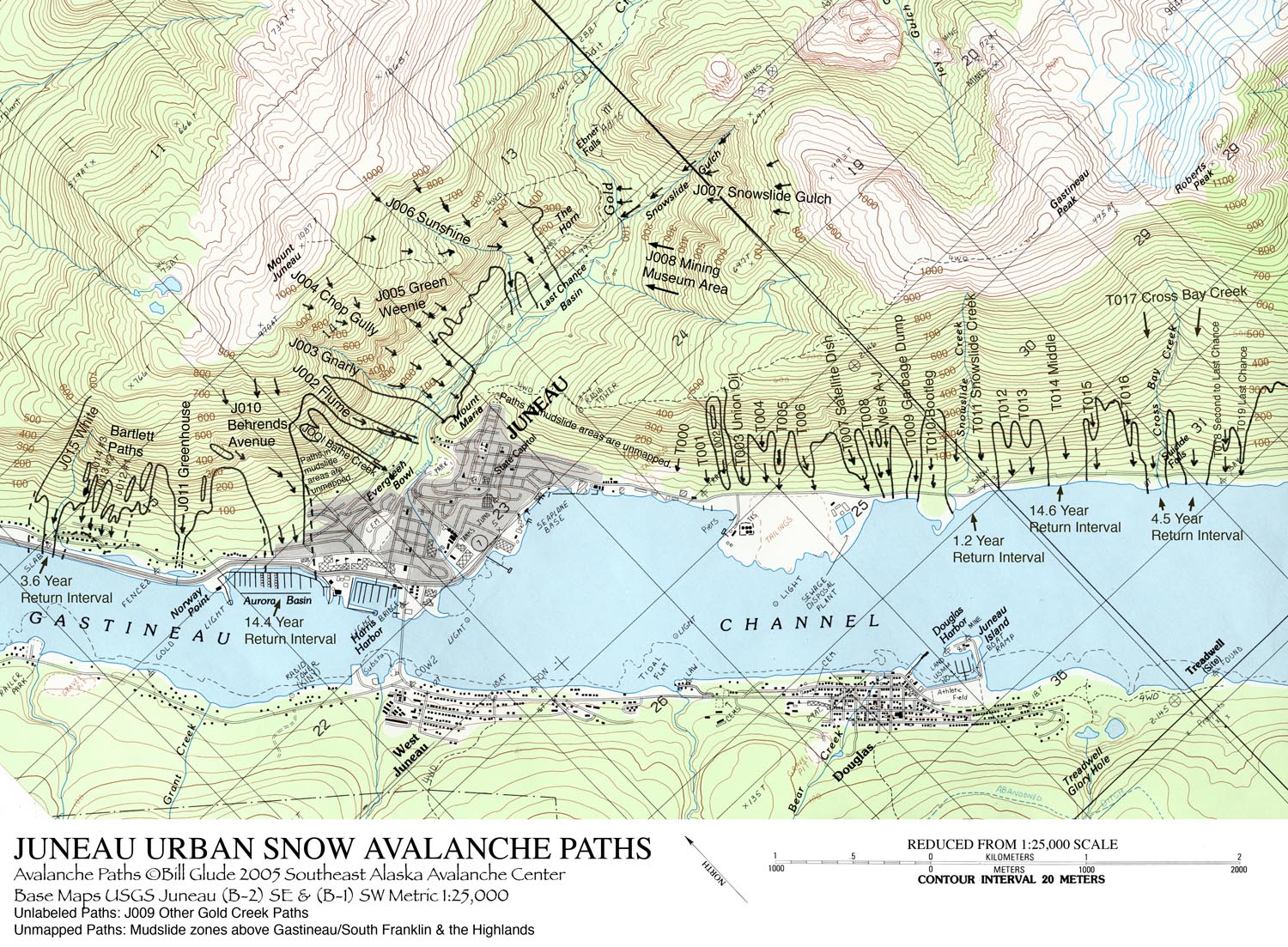

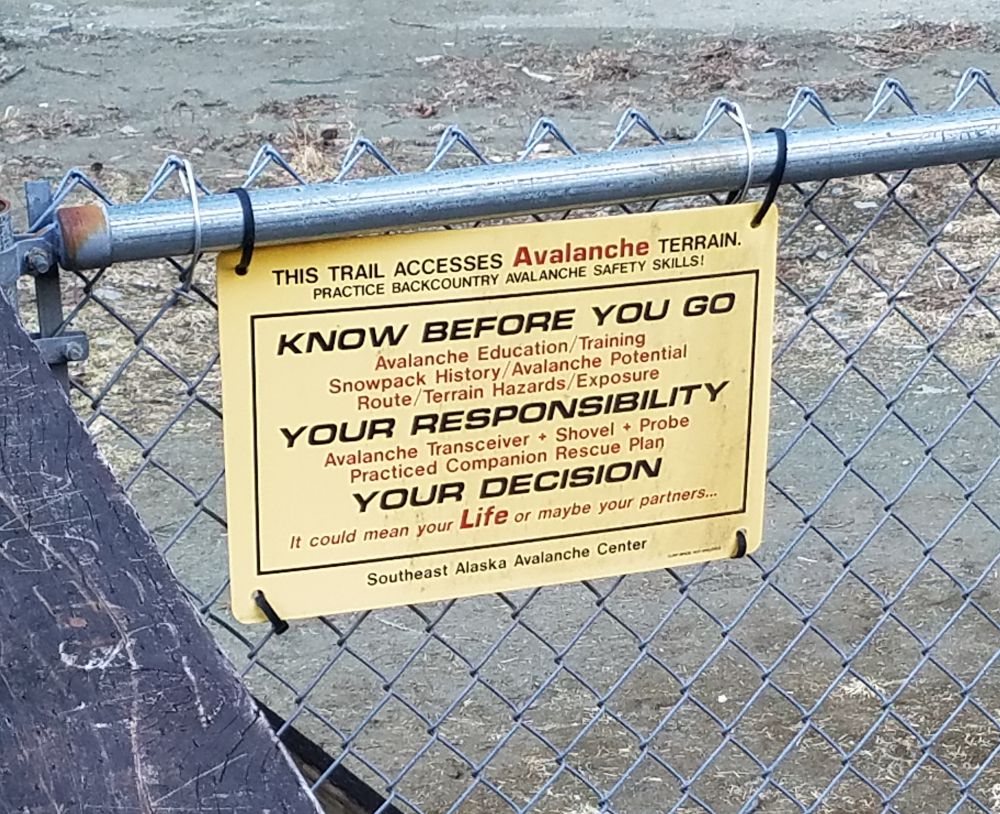

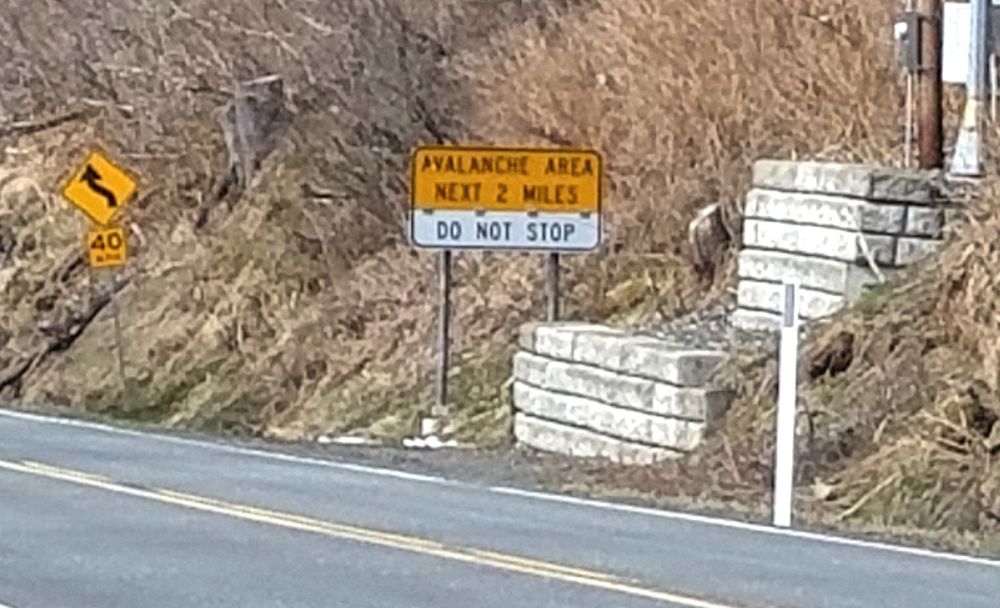

I even hiked on top of a recent avalanche in Juneau, the U.S. city most at risk for urban avalanches. Join me for my explorations of disaster risk and resiliency in the 49th State.

— Michael Grass

Executive Editor

Route Fifty | Government Executive Media Group- Start Over

Do Not Sell My Personal Information

When you visit our website, we store cookies on your browser to collect information. The information collected might relate to you, your preferences or your device, and is mostly used to make the site work as you expect it to and to provide a more personalized web experience. However, you can choose not to allow certain types of cookies, which may impact your experience of the site and the services we are able to offer. Click on the different category headings to find out more and change our default settings according to your preference. You cannot opt-out of our First Party Strictly Necessary Cookies as they are deployed in order to ensure the proper functioning of our website (such as prompting the cookie banner and remembering your settings, to log into your account, to redirect you when you log out, etc.). For more information about the First and Third Party Cookies used please follow this link.

Manage Consent Preferences

Strictly Necessary Cookies - Always Active

We do not allow you to opt-out of our certain cookies, as they are necessary to ensure the proper functioning of our website (such as prompting our cookie banner and remembering your privacy choices) and/or to monitor site performance. These cookies are not used in a way that constitutes a “sale” of your data under the CCPA. You can set your browser to block or alert you about these cookies, but some parts of the site will not work as intended if you do so. You can usually find these settings in the Options or Preferences menu of your browser. Visit www.allaboutcookies.org to learn more.

Sale of Personal Data, Targeting & Social Media Cookies

Under the California Consumer Privacy Act, you have the right to opt-out of the sale of your personal information to third parties. These cookies collect information for analytics and to personalize your experience with targeted ads. You may exercise your right to opt out of the sale of personal information by using this toggle switch. If you opt out we will not be able to offer you personalised ads and will not hand over your personal information to any third parties. Additionally, you may contact our legal department for further clarification about your rights as a California consumer by using this Exercise My Rights link

If you have enabled privacy controls on your browser (such as a plugin), we have to take that as a valid request to opt-out. Therefore we would not be able to track your activity through the web. This may affect our ability to personalize ads according to your preferences.

Targeting cookies may be set through our site by our advertising partners. They may be used by those companies to build a profile of your interests and show you relevant adverts on other sites. They do not store directly personal information, but are based on uniquely identifying your browser and internet device. If you do not allow these cookies, you will experience less targeted advertising.

Social media cookies are set by a range of social media services that we have added to the site to enable you to share our content with your friends and networks. They are capable of tracking your browser across other sites and building up a profile of your interests. This may impact the content and messages you see on other websites you visit. If you do not allow these cookies you may not be able to use or see these sharing tools.

If you want to opt out of all of our lead reports and lists, please submit a privacy request at our Do Not Sell page.

Cookie List

A cookie is a small piece of data (text file) that a website – when visited by a user – asks your browser to store on your device in order to remember information about you, such as your language preference or login information. Those cookies are set by us and called first-party cookies. We also use third-party cookies – which are cookies from a domain different than the domain of the website you are visiting – for our advertising and marketing efforts. More specifically, we use cookies and other tracking technologies for the following purposes:

Strictly Necessary Cookies

We do not allow you to opt-out of our certain cookies, as they are necessary to ensure the proper functioning of our website (such as prompting our cookie banner and remembering your privacy choices) and/or to monitor site performance. These cookies are not used in a way that constitutes a “sale” of your data under the CCPA. You can set your browser to block or alert you about these cookies, but some parts of the site will not work as intended if you do so. You can usually find these settings in the Options or Preferences menu of your browser. Visit www.allaboutcookies.org to learn more.

Functional Cookies

We do not allow you to opt-out of our certain cookies, as they are necessary to ensure the proper functioning of our website (such as prompting our cookie banner and remembering your privacy choices) and/or to monitor site performance. These cookies are not used in a way that constitutes a “sale” of your data under the CCPA. You can set your browser to block or alert you about these cookies, but some parts of the site will not work as intended if you do so. You can usually find these settings in the Options or Preferences menu of your browser. Visit www.allaboutcookies.org to learn more.

Performance Cookies

We do not allow you to opt-out of our certain cookies, as they are necessary to ensure the proper functioning of our website (such as prompting our cookie banner and remembering your privacy choices) and/or to monitor site performance. These cookies are not used in a way that constitutes a “sale” of your data under the CCPA. You can set your browser to block or alert you about these cookies, but some parts of the site will not work as intended if you do so. You can usually find these settings in the Options or Preferences menu of your browser. Visit www.allaboutcookies.org to learn more.

Sale of Personal Data

We also use cookies to personalize your experience on our websites, including by determining the most relevant content and advertisements to show you, and to monitor site traffic and performance, so that we may improve our websites and your experience. You may opt out of our use of such cookies (and the associated “sale” of your Personal Information) by using this toggle switch. You will still see some advertising, regardless of your selection. Because we do not track you across different devices, browsers and GEMG properties, your selection will take effect only on this browser, this device and this website.

Social Media Cookies

We also use cookies to personalize your experience on our websites, including by determining the most relevant content and advertisements to show you, and to monitor site traffic and performance, so that we may improve our websites and your experience. You may opt out of our use of such cookies (and the associated “sale” of your Personal Information) by using this toggle switch. You will still see some advertising, regardless of your selection. Because we do not track you across different devices, browsers and GEMG properties, your selection will take effect only on this browser, this device and this website.

Targeting Cookies

We also use cookies to personalize your experience on our websites, including by determining the most relevant content and advertisements to show you, and to monitor site traffic and performance, so that we may improve our websites and your experience. You may opt out of our use of such cookies (and the associated “sale” of your Personal Information) by using this toggle switch. You will still see some advertising, regardless of your selection. Because we do not track you across different devices, browsers and GEMG properties, your selection will take effect only on this browser, this device and this website.