Connecting state and local government leaders

COMMENTARY | Modern agriculture is a dying industry.

These are difficult times in farm country. Historic spring rains – 600% above average in some places – inundated fields and homes. The U.S. Department of Agriculture predicts that this year’s corn and soybean crops will be the smallest in four years, due partly to delayed planting.

Even before the floods, farm bankruptcies were already at a 10-year high. In 2018 less than half of U.S. growers made any income from their farms, and median farm income dipped to negative $1,553 – that is, a net loss.

At the same time, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that about 12 years remain to rein in global greenhouse gas emissions enough to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Beyond this point, scientists predict significantly higher risks of drought, floods and extreme heat.

And a landmark UN report released in May warns that roughly 1 million species are now threatened with extinction. This includes pollinators that provide US$235 billion to $577 billion in annual global crop value.

As scholars who study agroecology, agrarian change and food politics, we believe U.S. agriculture needs to make a systemwide shift that cuts carbon emissions, reduces vulnerability to climate chaos and prioritizes economic justice. We call this process a just transition – an idea often invoked to describe moving workers from shrinking industries like coal mining into more viable fields.

But it also applies to modern agriculture, an industry which in our view is dying – not because it isn’t producing enough, but because it is contributing to climate change and exacerbating rural problems, from income inequality to the opioid crisis.

Reconstructing rural America and dealing with climate change are both part of this process. Two elements are essential: agriculture based in principles of ecology, and economic policies that end overproduction of cheap food and reestablish fair prices for farmers.

Climate Solutions on the Farm

Agriculture generates about 9% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions from sources that include synthetic fertilizers and intensive livestock operations. These emissions can be significantly curbed through adopting methods of agroecology, a science that applies principles of ecology to designing sustainable food systems.

Agroecological practices include replacing fossil-fuel-based inputs like fertilizer with a range of diverse plants, animals, fungi, insects and soil organisms. By mimicking ecological interactions, biodiversity produces both food and renewable ecosystem services, such as soil nutrient cycling and carbon sequestration.

Cover crops are a good example. Farmers grow cover crops like legumes, rye and alfalfa to reduce soil erosion, improve water retention and add nitrogen to the soil, thereby curbing fertilizer use. When these crops decay, they store carbon – typically about 1 to 1.5 tons of carbon dioxide per 2.47 acres per year.

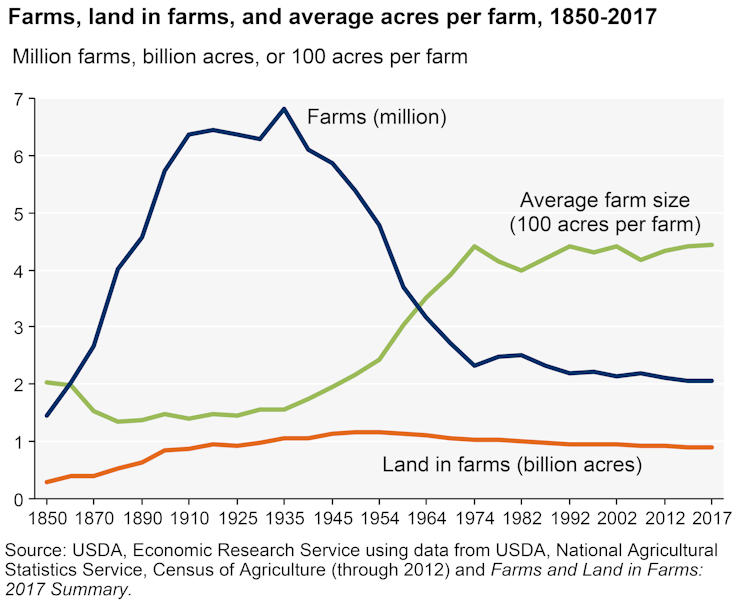

Cover crop acreage has surged in recent years, from 10.3 million acres in 2012 to 15.4 million acres in 2017. But this is a tiny fraction of the roughly 900 million acres of farmed land in the U.S.

Another strategy is switching from row crops to agroforestry, which combines trees, livestock and crops in a single field. This approach can increase soil carbon storage by up to 34%. And moving animals from large-scale livestock farms back onto crop farms can turn waste into nutrient inputs.

Unfortunately, many U.S. farmers are stuck in industrial production. A 2016 study by an international expert panel identified eight key “lock-ins,” or mechanisms, that reinforce the large-scale model. They include consumer expectations of cheap food, export-oriented trade, and most importantly, concentration of power in the global food and agricultural sector.

Because these lock-ins create a deeply entrenched system, revitalizing rural America and decarbonizing agriculture require addressing systemwide issues of politics and power. We believe a strong starting point is connecting ecological practices to economic policy, especially price parity – the principle that farmers ought to be fairly compensated, in line with their production costs.

Economic Justice on the Farm

If the concept of parity sounds quaint, that’s because it is. Farmers first achieved something like parity in 1910-1914, just before America entered World War I. During the war U.S. agriculture prospered, financing flowed and land speculation was rampant.

Those bubbles burst with the end of the war. As crop prices fell below the cost of production, farmers began going broke in a prelude to the Great Depression. Unsurprisingly, they tried to produce more food to get out of debt, even as prices collapsed.

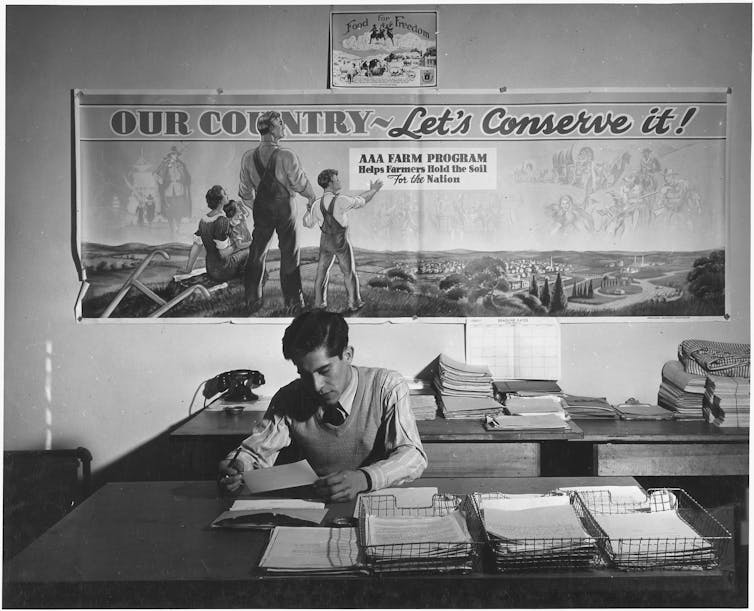

President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal included programs that directed public investments to rural communities and restored “parity.” The federal government established price floors, bought up surplus commodities and stored them in reserve. It also paid farmers to reduce production of basic crops, and established programs to prevent destructive farming practices that had contributed to the Dust Bowl.

These policies provided much-needed relief for indebted farmers. In the “parity years,” from 1941 to 1953, the floor price was set at 90% of parity, and the prices farmers received averaged 100% of parity. As a result, purchasers of commodities paid the actual production costs.

But after World War II, agribusiness interests systematically dismantled the supply management system. They included global grain trading companies Archer Daniels Midland and Cargill and the American Farm Bureau Federation, which serves primarily large-scale farmers.

These organizations found support from federal officials, particularly Earl Butz, who served as secretary of agriculture from 1971 to 1976. Butz believed strongly in free markets and viewed federal policy as a lever to maximize output instead of constraining it. Under his watch, prices were allowed to fall – benefiting corporate purchasers – and parity was replaced by federal payments to supplement farmers’ incomes.

The resulting lock-in to this economic model progressively strengthened in the following decades, creating what many scientific assessments now recognize as a global food system that is unsustainable for farmers, eaters and the planet.

A New 'New Deal' for Agriculture

Today the idea of restoring parity and reducing corporate power in agriculture is resurging. Several 2020 Democratic presidential candidates have included it in their agriculture positions and legislation. Think tanks are proposing to empower family farms. Dairy delegates to the regulation-averse Wisconsin Farm Bureau Foundation voted in December 2018 to discuss supply management.

Along with other scholars, we have urged Congress to use the proposed Green New Deal to promote a just transition in agriculture. We see this as an opportunity to restore wealth to rural America in all of its diversity – particularly to communities of color who have been systematically excluded for decades from benefits available to white farmers.

This year’s biblical floods in the Midwest make any kind of farming look daunting. However, we believe that if policymakers can envision a contemporary version of ideas in the original New Deal, a climate-friendly and socially just American agriculture is within reach.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Maywa Montenegro is a UC president's postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Davis. Annie Shattuck is a Ph.D candidate at the University of California, Berkeley. Joshua Sbicca is an assistant professor of sociology at Colorado State University.

NEXT STORY: Oregon’s Single-Family Zoning Ban Was a ‘Long Time Coming’