Fate of Native Children May Hinge on U.S. Adoption Case

The end of the Indian Child Welfare Act, which is being challenged by a few states, could mean more Native kids adopted by non-Natives.

This story was originally published by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

A case before a federal appeals court this week could upend an historic adoption law meant to combat centuries of brutal discrimination against American Indians and keep their children with families and tribal communities.

For the first time, a few states have sued to overturn the federal Indian Child Welfare Act, which Congress enacted in 1978 as an antidote to entrenched policies of uprooting Native children and assimilating them into mainstream white culture.

Now, in a country roiled by debates over race and racial identity, there’s a chance the 41-year-old law could be overturned by the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, considered the country’s most conservative court. (The law applies to federally recognized tribes.)

Overturning the law, its proponents say, could significantly increase the number of American Indian children adopted into non-Native families.

Hundreds of tribal nations vehemently oppose the lawsuit. They say it threatens the sovereignty of Indian Country and seeks to “return Indian children to the arbitrary and discriminatory whims of state courts and state agencies, unfettered by the centuries-old trust obligations this nation owes to Indian tribes and Indian peoples.”

Meanwhile, some states and private adoption attorneys pushing for change argue the Indian Child Welfare Act interferes in state affairs and “requires them to place Indian children in accordance with statutory requirements based on race, rather than the children’s best interests.”

Oral arguments in the case will be heard Wednesday in New Orleans. Whatever the outcome, the case is likely headed for the U.S. Supreme Court.

Brackeen v. Bernhardt pits Texas, Indiana, Louisiana and a coalition of conservative legal groups, including the Goldwater Institute, against the federal government, hundreds of tribal nations, 21 state attorneys general, Native American civil rights groups and child welfare organizations, including the Annie E. Casey Foundation and the Children’s Defense Fund.

The plaintiffs, who include several families interested in adopting Native American children and a non-Native biological parent who wants her American Indian child to be adopted by a non-Native family, argue that the law, often called ICWA (pronounced ICK-wah), is race-based and violates the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Tribal nations counter that “Indian” is a political, rather than a racial, designation. The Supreme Court agrees with that classification. In 1974, it said that with federal hiring preferences for American Indians in federally recognized tribes, “preference is political, rather than racial in nature.”

The plaintiffs also charge that in enacting the law, Congress exceeded its authority over federal affairs with tribal nations.

“I want to see ICWA overturned completely,” said Mark Fiddler, co-counsel on the Brackeen case representing adoptive families, and an enrolled member of the Chippewa Nation. “ICWA has been a miserable failure.”

Over the years, though, the child welfare law has been held up by child welfare advocates as the gold standard for foster care and adoption, because it requires agencies to keep families together when possible.

When that’s not safe or feasible, the law requires agencies to try to place children with relatives or other members of their community. (That philosophy is further represented in a new federal law, the Family First Prevention Services Act, which includes broad changes to the U.S. foster care system.)

Many child welfare advocates fear that overturning the landmark law would send more Native children into foster care and that more would be adopted out of their tribal communities.

Some say overturning ICWA also would affect other federal laws governing tribal sovereignty, such as the Indian Gaming Regulations Act.

“This is about attacking Indian law and Indian sovereignty,” said Chrissi Nimmo, deputy attorney general for the Cherokee Nation. “This is just the first step.” The Cherokee, Navajo, Oneida and Quinault Indian Nations, as well as the Morongo Band of Mission Indians, asked to be included as defendants in the lawsuit.

But Fiddler dismisses that argument as “laughable,” saying, “That’s a pious, sky-is-falling argument.”

Fiddler used to defend ICWA cases and in 1994 founded the ICWA Law Center in Minneapolis to make sure the law was being enforced in adoption and foster care cases.

Back then, Fiddler said, he thought ICWA made for “compelling policy” because it tried to preserve Native culture whenever possible and keep families together. He still supports those goals, he said.

But he’s committed to overturning the law: “ICWA is harming the very children it was designed to protect,” Fiddler said.

He recalled a 1997 case in which he represented an American Indian mother who’d put her child up for adoption and wanted to get her child back—after the child had been with his adoptive parents for more than a year.

Child psychologists told Fiddler that separating the child from his adoptive parents would cause lasting harm to the child.

“But it was deeply troubling to me,” Fiddler recalled. “ICWA was overriding a child’s need for secure attachment in a safe and stable home.”

‘Potential Indian Children’

In October, U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor of the Northern District of Texas—known for striking down the Affordable Care Act in December—ruled that the Indian Child Welfare Act is unconstitutional.

“ICWA’s racial classification applies to potential Indian children [who are eligible for tribal citizenship],” O’Connor wrote, “including those who will never be members of their ancestral tribe, those who will ultimately be placed with non-tribal family members, and those who will be adopted by members of other tribes.” The law, he wrote, is a “race-based statute” that treats Native children differently.

A coalition of conservative legal groups filed a series of friend of the court briefs in the Brackeen case. One argued ICWA “imposes race-based mandates and prohibitions that make it harder for states to protect Native American children against abuse.”

The latest case echoes another infamous case, Adoptive Parents v. Baby Girl, a wrenching custody battle over a Cherokee girl who bounced back and forth between her American Indian father and her white adoptive parents.

The U.S. Supreme Court in 2013 ruled in a 5-4 vote that a non-custodial Native American parent cannot invoke ICWA to block an adoption initiated by a non-Indian parent. The girl was returned to her adoptive parents.

Brackeen v. Bernhardt originated in 2017, when white foster parents wanted to adopt a 2-year-old boy who’d been placed in their care. The child’s biological parents are enrolled members of the Navajo and Cherokee Nations, which means the toddler was eligible for enrollment in both tribes.

The parents of the boy identified in court records as “A.L.M.” consented to the Brackeens adopting the child, court records show. But the Navajo Nation had identified a Native family in New Mexico and wanted the child to be placed with them.

The Brackeens sued and eventually were able to adopt the child.

The vice president of litigation for the Goldwater Institute, Tim Sandefur, said the Indian Child Welfare Act is problematic because it relies on race to place children in homes and because it requires child welfare agencies to take extra steps to keep a potentially abused child with neglectful parents. The institute filed a brief in support of the Brackeens.

“ICWA requires that Indian children be more abused,” Sandefur said. “That’s disgraceful.”

‘Take the Indian Out’

In 1978, when the law was enacted, 1 in 4 Native children was in the child welfare system; the overwhelming majority—99 percent—were living in non-Native homes, said Kathryn Fort, director of the Indian Law Clinic at Michigan State University, one of the lawyers representing the tribes in the Brackeen case.

Those statistics stemmed from policies dating to the 1800s of removing American Indian children from their homes and placing them in military boarding schools or having them adopted by white families.

The idea was to “take the Indian out of the child,” said Shannon Smith, executive director of the IWCA Law Center in Minneapolis, which represents families affected by the child welfare system.

That history led to a vicious cycle of generations of broken families, Indian child welfare experts say.

Congress wrote in ICWA that “an alarmingly high percentage of Indian families [were being] broken up by the removal, often unwarranted, of their children from them by nontribal public and private agencies.”

ICWA set the stage for other child welfare legislation, Fort said. Two years later, Congress passed the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act, which created federal funding for foster care and adoption assistance.

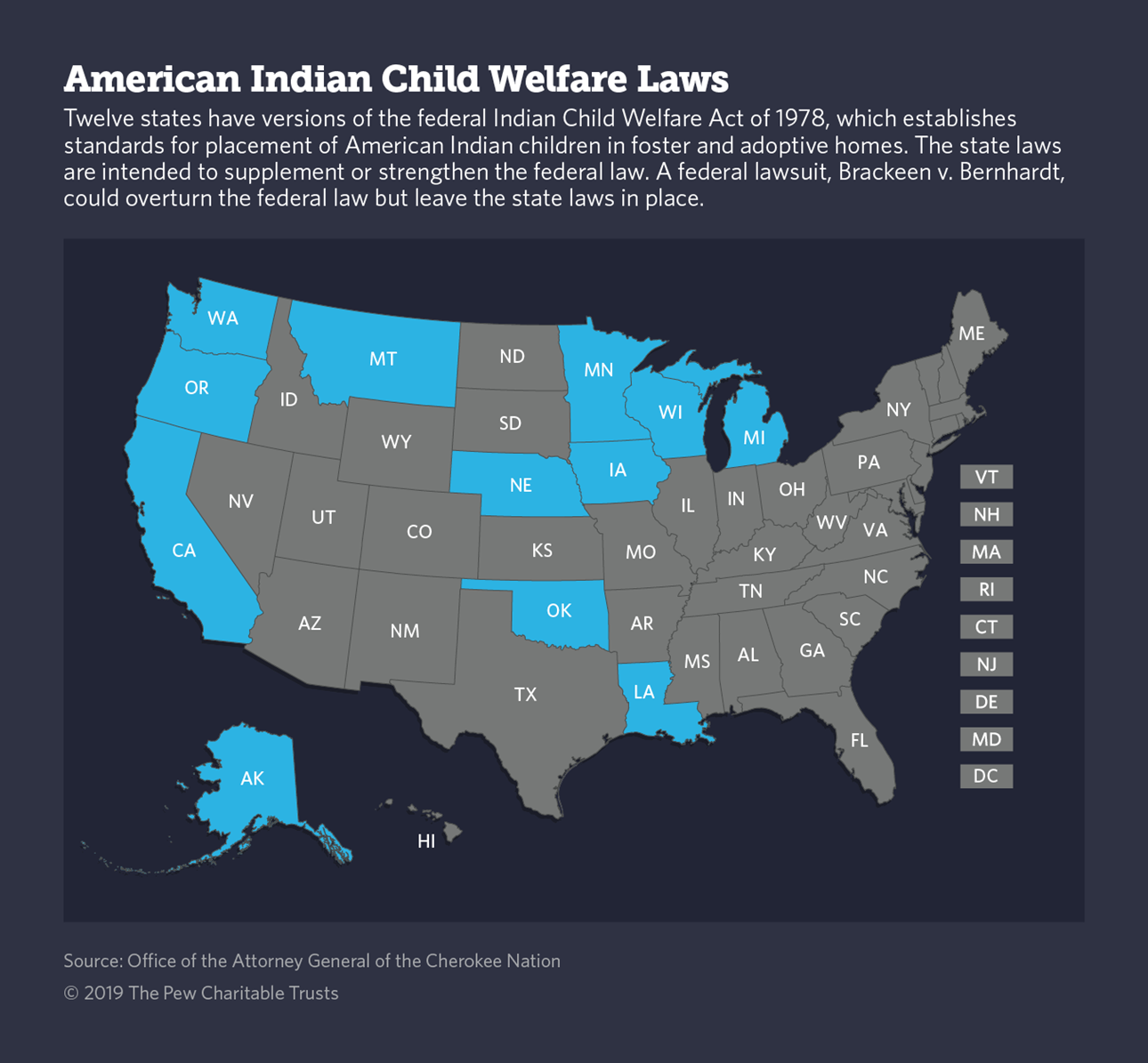

And a dozen states enacted versions of the Indian Child Welfare Act, establishing standards for placement in foster and adoptive homes. These laws were intended to supplement, strengthen or in some cases correct judicial interpretations of the federal statute that state lawmakers thought were incorrect.

Today, Native American children remain disproportionately represented in the foster care system. Since 2009, they’ve had the highest rates of representation in the foster care system, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, a Washington, D.C.-based group that tracks state policy.

Nationwide, they are overrepresented in foster care by nearly three times their proportion in the general population, according to National Indian Child Welfare Association. The Portland, Oregon-based nonprofit, which works to ensure the well-being of Native children, filed a friend of the court brief in the case.

What’s more, research has shown that because of bias, American Indian children are twice as likely to be involved in an abuse investigation, and they are four times more likely to be placed in foster care than white children.

Child welfare experts fear those statistics will get worse if ICWA is overturned.

“If we didn’t have the Indian Child Welfare Act, who’s to say where we would be right now,” said David Simmons, National Indian Child Welfare Association’s director of government affairs and advocacy.

NEXT STORY: Get Off My Lawn