Extending Medicaid After Childbirth Could Reduce Maternal Deaths

Shutterstock

Evidence shows women should receive follow-up care for a year after giving birth.

NASHVILLE, Tenn. — Samantha Powell, 29, says she wouldn’t be alive today if it weren’t for the mental health services she received after her last child was born.

“I had postpartum depression with my other two children, so I knew what was happening to me. I knew it wasn’t going to be fun,” she said. “But this time, I felt suicidal. Luckily, I was able to get help before it was too late.”

Nationwide, drug overdoses, suicides and pregnancy-related chronic illnesses such as diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure are contributing to a rise in deaths among women during pregnancy, childbirth and the first 12 months after delivery.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 3 out of 5 of those deaths could be prevented with adequate medical attention.

But Medicaid pregnancy coverage, which pays for nearly half of all births in the United States, expires 60 days after childbirth, leaving many women without health insurance at one of the most vulnerable times in their lives.

After the 60 days, women can reapply as a parent, but the income limit is typically much lower, so thousands of women don’t qualify.

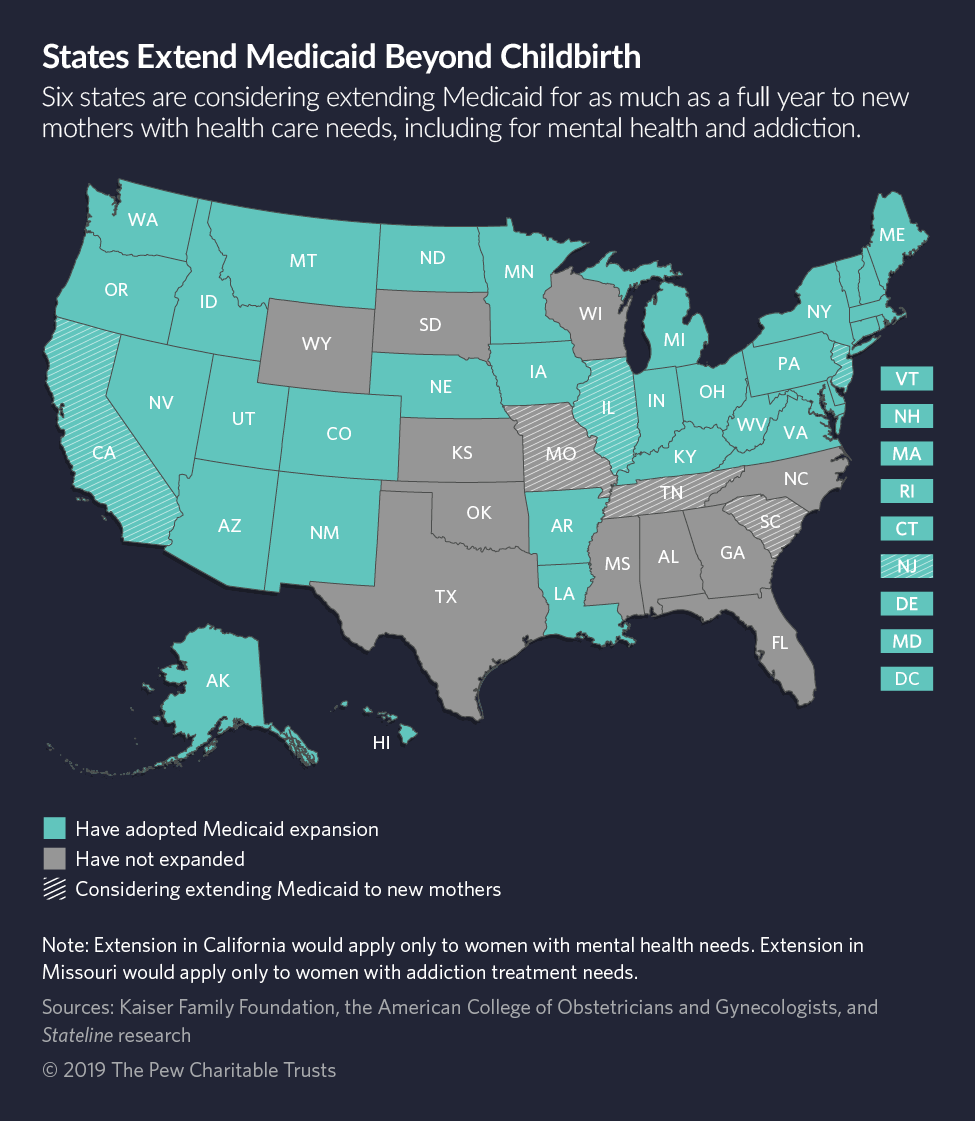

Policymakers in at least six states—California, Illinois, Missouri, New Jersey, South Carolina and Tennessee—are trying to change that by extending Medicaid coverage to a full year after delivery. And health agencies in Georgia, Texas, Utah and Washington are recommending similar initiatives.

In addition, a bipartisan bill in Congress, the Helping Medicaid Offer Maternity Services Act of 2019, would offer states an incentive to extend their Medicaid coverage to a full year after delivery by reducing red tape and boosting the federal government’s share of funding by 5 percentage points.

“There’s a lot of energy behind this policy right now at both the federal and state levels,” said Alyson Northrup, associate director of government affairs at the Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs, a Washington, D.C.-based group of state public health officials.

“States have a real opportunity to support continuity of care, which is critical during the vulnerable postpartum period,” she said.

About 700 women died from pregnancy-related conditions in the United States in 2016.

In Tennessee, where two-thirds of births in 2017 were covered by the state’s Medicaid program, called TennCare, more than half of the deaths of enrolled mothers occurred six weeks or more postpartum.

Opioids and Pregnancy

Maternal mortality rates, which include deaths during and up to one year after pregnancy, are higher in the United States than in other developed nations, according to a recent study by the Commonwealth Fund, a health care advocacy group.

And while pregnancy-related death rates have been dropping worldwide, they’ve more than doubled in the United States in the past 30 years, rising from 7 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1987 to 17 in 2016, according to the CDC.

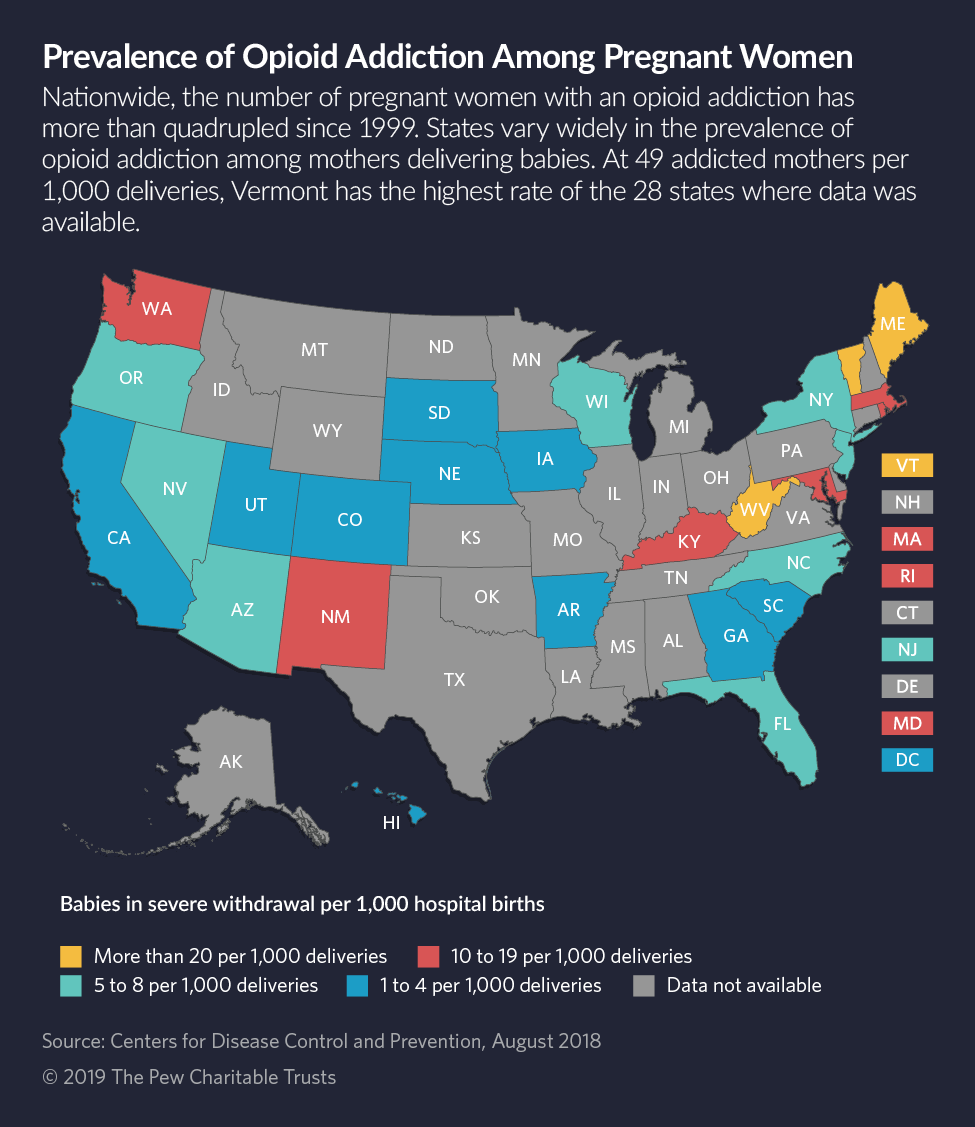

The opioid crisis is a contributing factor. Opioid addiction among pregnant women has quadrupled in the past 20 years, the CDC said.

In Tennessee, where the maternal death rate is higher than the national average, drug use contributed to a third of maternal fatalities, according to the state’s 2017 maternal mortality review.

“As a whole, women with substance use disorders do quite well during pregnancy, due in large extent to access to care, insurance coverage and attention from social services,” said Mishka Terplan, an obstetrics and gynecology physician affiliated with the University of California at San Francisco.

“Where things fall apart is postpartum,” he said. “We actually abandon women after delivery.”

Powell, who started abusing prescription painkillers at 14 and moved to injecting heroin by the time she was 18, has been in and out of recovery since her first child was born when she was 21.

With her most recent child, a daughter named Luna who turns 1 this month, Powell took the addiction medication buprenorphine throughout her pregnancy and stayed in recovery.

But the cash-only doctor she went to for her medication didn’t offer the counseling and mental health services she said she needed to stay in recovery, and she couldn’t find an addiction treatment center in the Nashville area that would take Medicaid.

After her daughter was born, Powell said she tried again to find addiction treatment that met her needs, but worried how she would pay for it, because her Medicaid coverage had been cancelled.

As luck would have it, a doctor at the hospital where Powell delivered Luna used to work at Vanderbilt Women’s Health. He gave her the address and phone number.

“I’d been searching on the internet and asking everyone I knew and coming up empty,” Powell said. “If I hadn’t of had my baby at that particular hospital, and if I hadn’t of showed up at the women’s center and gotten into the program, I don’t know what would have happened to me.”

Vanderbilt’s federally funded program, which combines prenatal and postpartum care with addiction and mental health treatment for women facing the double challenge of pregnancy and recovery, accepts Medicaid, which most low-income women qualify for during pregnancy.

But because Medicaid expires 60 days after delivery, the clinic is forced to use its limited grant money from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to allow women to stay in treatment for at least a year after delivery.

Dr. Jessica Young, a physician at the center, said that when the clinic first opened in 2011, it provided care for women with opioid addictions throughout their pregnancies and then transferred them to other treatment facilities eight weeks after delivery.

But a year-and-a-half ago, Young and her colleagues decided to extend the program to at least 12 months after delivery. “Because of the high risk of relapse and overdose after delivery, it made so much more sense to keep them in the program they were already in.”

Young, who is still treating Powell for her addiction, said she learned from patients who came back to the clinic after a subsequent pregnancy that the year after childbirth can be tumultuous.

“We heard from women who relapsed and had to start using heroin because they couldn’t afford treatment, we heard from women who had depression, hypertension and other health issues that developed after we last saw them,” she said. “Some told us their pregnancies were unplanned because they didn’t have access to contraception after their last child. And many reported fleeing domestic violence and becoming homeless.

“It feels like it would be a game changer,” Young said, “not just for women with addiction, but for all women on TennCare, to have that peace of mind that their insurance isn’t going to go away right after delivery.”

Next year, a substantial portion of Vanderbilt’s federal grant money will dry up, and unless it’s replaced with new funding, Young said she’s not sure whether the clinic can continue its 12-month postpartum care.

Filling a Gap

For women like Powell who rely on the joint federal-state funded health plan for the poor, the perilous first year after childbirth can become even riskier.

Sleep deprivation, hormonal shifts and the responsibility of caring for an infant create enormous stress for women. And yet most medical protocols as well as Medicaid and other social safety net programs are set up to shift attention away from the mother after delivery and provide resources exclusively for the new baby.

Traditional obstetrics practices call for women to see the doctor only once after the baby is delivered, usually at about six weeks, because for decades, experts generally thought pregnancy-related health issues ended about 60 days after delivery. After that, it’s up to the woman to decide whether she needs to see a primary care doctor, a psychiatrist or an addiction specialist.

But growing evidence suggests that women should receive continuous medical attention during what is now called the “fourth trimester” — a period lasting at least a year after childbirth.

Last year, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued new medical guidelines for postpartum care, saying that ongoing attention rather than a single encounter with a medical professional is urgently needed to “reduce severe maternal morbidity and mortality.”

The problem is exacerbated in Tennessee and the 16 other states that have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to cover all adults with incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level, about $17,000 for an individual.

To qualify as a parent in Tennessee, for example, a woman can make no more than $12,000. In South Carolina, it’s $8,000.

Parents whose babies are taken into state custody, as often happens when a pregnant woman uses drugs, are not eligible.

Proposals in South Carolina and Tennessee, which have not expanded Medicaid, would extend coverage for 12 months postpartum for women at higher incomes than those set for qualifying parents. In both states, the qualifying income limit for pregnant women is about $25,000.

A draft Medicaid waiver request in Missouri would extend the low-income health plan for women with addiction, provided the federal government approves the change. A California law relies on state funding to extend coverage after delivery for women with a mental health condition.

Proposals in Illinois and New Jersey, where expanded Medicaid covers adults with incomes of up to 138% of the poverty line, would extend pregnancy coverage to 12 months postpartum.

In Illinois, current Medicaid income eligibility for pregnancy coverage is $27,000 for an individual, and in New Jersey, it’s $25,000, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The Medicaid agency in Tennessee estimates the cost of extended postpartum coverage at $19 million, $13 million of which would be paid by the federal government. If approved, the agency’s proposed three-year pilot would apply to as many as 6,500 women a year, according to its fiscal 2021 budget proposal.

So far, Tennessee’s Republican Gov. Bill Lee has said he supports the proposal, particularly because it addresses the opioid epidemic. But final inclusion of the agency’s plan in the governor’s budget won’t come until January. After that, the legislature must approve it, and finally, the governor must request a waiver of federal Medicaid rules to implement the plan — a process that can take a year or more.

Talking while commuting an hour from her full-time job as a legal assistant in downtown Nashville, Powell cursed the hurdles she and other women face in getting access to addiction treatment and mental health care while trying to make a living and care for a newborn, and often other kids as well.

The music Nashville’s built on is filled with stories of women who overcome the hardships of love and life. “But it shouldn’t be so hard to get medical care when you’ve just had a baby,” Powell said. “It really shouldn’t require luck.”

Christine Vestal covers mental health and drug addiction for Stateline.

NEXT STORY: Florida Governor Wants High School Students to Take Civics Exam