Demand Surges for Addiction Treatment During Pregnancy

Thomas / Flikr.com

Connecting state and local government leaders

Nationwide, the number of pregnant women using heroin, prescription opioids or medications used to treat opioid addiction has increased more than five-fold and it’s expected to keep rising.

This article was originally published at Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and was written by Christine Vestal.

BOSTON — As soon as the home pregnancy test strip turned blue, Susan Bellone packed a few things and headed straight for Boston Medical Center’s emergency room. She’d been using heroin and knew she needed medical help to protect her baby.

“I felt so guilty. I still do,” said Bellone, a petite, energetic woman. At 32, and six years into her heroin addiction, having a baby was the last thing on her mind. “I was not in the right place to start a family,” she said. “But once it was happening, it was happening, so I couldn’t turn back.”

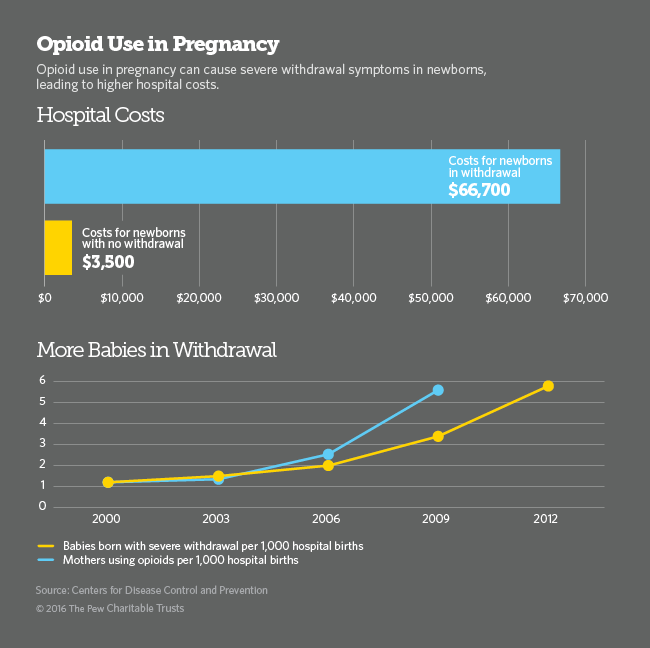

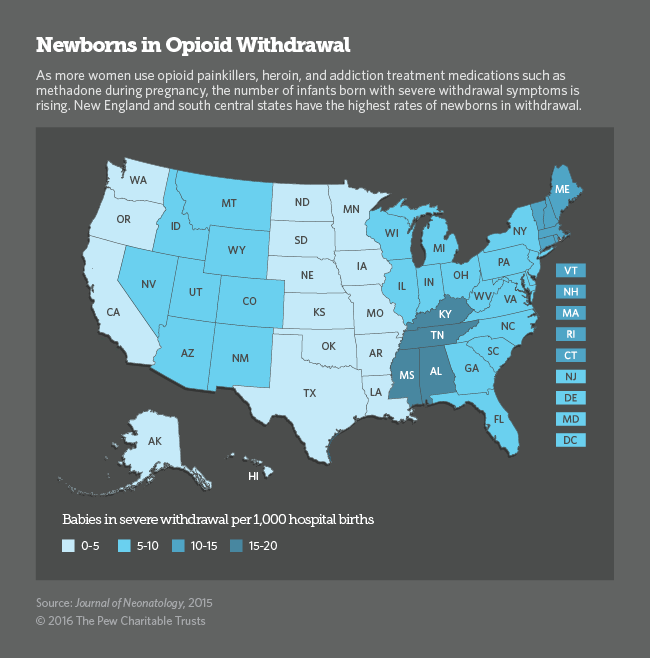

Nationwide, the number of pregnant women using heroin, prescription opioids or medications used to treat opioid addiction has increased more than five-fold and it’s expected to keep rising. With increased opioid and heroin use, the number of babies born with severe opioid withdrawal symptoms has also spiraled, leaving hospitals scrambling to find better ways to care for the burgeoning population of mothers and newborns.

Among the most important principles is that expectant mothers who are addicts should not try to quit cold turkey because doing so could cause a miscarriage. Trying to quit opioids without the help of medications also presents a high risk of relapse and fatal overdose.

Until the opioid epidemic took hold about eight years ago, most hospitals saw only one or two cases a year of what is known as neonatal abstinence syndrome. Now, a baby is born suffering from opioid withdrawal every 25 minutes in the U.S., according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

When a pregnant woman uses drugs or alcohol during pregnancy, some of the substances travel through the placenta to the baby. In many, but not all, cases, exposure to opioids during pregnancy can cause the fetus to develop physical drug dependence. When the umbilical cord is cut at birth, the newborn is abruptly disconnected from its supply of opioids and can suffer withdrawal symptoms.

When Bellone rushed to the emergency room six years ago, she didn’t know she’d gone to one of the best places in the country to receive addiction treatment during pregnancy.

At Boston Medical Center in the city’s South End, heroin addiction during pregnancy is not new. A specialized team of obstetricians, addiction medicine providers and counselors known as Project RESPECT has been treating pregnant drug users here for more than 30 years.

Now, dozens of hospitals and health clinics are gearing up to provide the same kind of specialized treatment for a rapidly rising number of pregnant drug users and their newborns

Although painful, newborn withdrawal symptoms, which include muscle cramps, tremors, diarrhea, vomiting, sleep problems and sometimes seizures, are not life threatening and have not been shown to cause health problems or developmental deficiencies later in life. The condition can be treated with small doses of morphine and subsides within a one to three weeks.

Methadone and Buprenorphine

As an epidemic of opioid and heroin addiction continues to ravage the nation, affecting at least 2.5 million people, hospitals and obstetrical practices nationwide have begun collaborating with addiction specialists to find the best way to treat women for their addiction while providing the safest care for their babies.

“Addiction specialists are terrified of treating anyone with a baby inside, and obstetricians are terrified of getting into addiction medicine,” said Dr. Ronald Iverson, of the Massachusetts Perinatal Quality Collaborative. But as demand for prenatal care for opioid-dependent women skyrockets, hospitals and private practices are increasingly offering combined addiction treatment and obstetrical services, so that pregnant women can see both specialists in one appointment.

Last year, a federal law was enacted — the Protecting Our Infants Act — authorizing the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to work with states to collect data on the prevalence of babies born with opioids in their bloodstream. It also calls on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to develop recommendations for the best way to prevent and treat drug use during pregnancy.

For now, here’s what major medical organizations — including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Society of Addiction Medicine and the American Academy of Pediatrics — agree on:

The standard of care for pregnant women using prescription painkillers or heroin is maintenance treatment with opioid addiction medications methadone or buprenorphine. Abstaining from drugs without medication is not recommended because of the high risk to the mother of relapse and overdose.

Although methadone and buprenorphine expose the fetus to low doses of opioids, the risk to the newborn of withdrawal symptoms is far outweighed by the risk of a fatal overdose when pregnant women receive no treatment or attempt to abstain from drugs without medication.

Abruptly quitting opioids in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy can cause harm to the fetus, including miscarriage and stillbirth, and is not recommended. Even in the second trimester, specialists agree that the risk of relapse outweighs any potential benefit to the fetus of lowering the dose of addiction maintenance medications or discontinuing their use.

Advocates for newborns, including the March of Dimes, agree with major medical organizations on the use of opioid treatment medication. But they argue more data and better research are needed to determine the best approach to treating opioid addiction during pregnancy.

“With pregnant moms, we’re weighing the high risk of death from overdose against the risk to the newborn of treating pregnant women with low dose opioid maintenance,” said Dr. Siobhan Dolan, medical adviser to the March of Dimes. With more research, she said, “we would be in a better position to consider abstinence and behavioral health counseling for some women.” And that could result in healthier babies.

According to the most recent data from the CDC, the number of opioid and heroin overdose deaths shot up by 14 percent between 2013 and 2014, killing more than 28,000 people, more than 10,000 of whom were women.

Fear and Misinformation

Most women who come into Boston Medical Center for drug treatment and prenatal care do so early in their pregnancy, said Dr. Kelley Saia, who heads Project RESPECT’s team that now treats about 250 patients at any given time, triple the number it did 10 years ago.

“They are so smart and so tuned into what they’re going through,” Saia said. “But they feel incredible guilt about taking medication during pregnancy and they worry about what their babies will go through.”

When Bellone arrived at Boston Medical she was ready to quit heroin. She’d done it before. “I wanted to stop everything. I didn’t even want to be on Subutex [a form of buprenorphine], but they said I might miscarry.”

On top of the normal worries about going through a pregnancy and becoming a parent, women with a drug habit worry about getting reported to child protective services. Massachusetts requires hospitals to report all babies born with opioids in their bloodstream to the state’s child welfare agency.

In many other states, doctors are required to report their patients to child welfare agencies before their babies are born, said Farah Diaz-Tello, an attorney with National Advocates for Pregnant Women, which advocates for the civil rights of drug-using women. In three states — Alabama, South Carolina and Tennessee — women can be prosecuted for child endangerment if they are reported using drugs during pregnancy. (The Tennessee law will not be in effect after July 1.)

Diaz-Tello and others say this threatens the health of women and their babies. Women need to feel safe so they don’t have to hide their drug use when seeking prenatal care or not seek care at all, she said.

Bellone said she wasn’t concerned about getting reported to child protective services because she knew she was doing the right thing. “If I wasn’t ready to quit I would have been worried,” she said. “But I knew five years before I got pregnant that I didn’t want to lead that life. I needed help and didn’t know where to go.

“It was almost like it took me getting pregnant to find help. It was hard to get into any place. There were no beds. But once you got pregnant it was instant, people were willing to help.”

Bellone’s pregnancy and her addiction treatment went smoothly. She delivered twin girls, Gemma and Mischa, on Aug. 3, 2010. They had to stay in the hospital for three weeks, but they’ve been healthy since they came home.

Perched on her chair sipping a huge to-go cup of iced tea in one of the hospital’s private consultation rooms, Bellone passed around photos of the twins jumping on their bed. Gemma, the oldest by seven minutes, just lost a tooth. “She pulled it out herself. She was very brave,” Bellone said.

Nearly six years after their birth, Bellone is still in recovery. She’s taking buprenorphine, making monthly visits to her addiction doctor and attending group meetings two times a week. She’s also working full time as a cook at a nursing home. “I’m tired a lot, like anyone with twins would be,” Bellone said. “People think I’m lying, but I never think about using.”

NEXT STORY: Average US connection speed buoyed by local efforts