Cities turn to tech to make curb ramps ADA-accessible

Courtesy image via Esri

Localities must install or regrade their curb ramps when roads are changed, and they are using aerial photography, geospatial data and AI to help.

As cities develop plans to transition their curb ramps to ensure compliance with Americans with Disabilities Act regulations, they are turning to technology.

ADA requires localities to install or regrade curb ramps to meet current requirements when roads are constructed or changed, such as repaved. But some localities don’t have good records on where all their curb ramps are located, how they were constructed or whether they comply.

That was the case in Douglas County, Nebraska, which includes Omaha, the state’s largest city, and Lawrence, Kansas.

In Douglas County, officials are using high-resolution aerial photography and Esri’s GIS technology and GeoAI, an application that fuses artificial intelligence and geospatial data, to map out more than 34,000 curb ramps.

Steve Cacioppo, senior GIS analyst at the Douglas County/Omaha NE GIS Department, used high-res images to create training samples for GeoAI.

“I basically went into our imagery and identified 753 curb ramps, and I made sure that they were all a little bit different, meaning I had the easy ones that were in new subdivisions where you had this nice contrast between the concrete and the curb ramp,” Cacioppo said. “Then I went to the older parts of the city, where you might have dirt that is washed over on them, they might have been broken. I tried to give the model a good representation of what’s out there.”

When he runs the tool, it places polygons around the ramps it finds. Cacioppo then checks for and corrects errors. It sometimes incorrectly marks car sunroofs, skylights on homes and inlet grates around manhole covers, for instance, he said.

Cacioppo estimated that it would take about 1,000 hours – or six months of a full-time employee’s time – to identify all the curb ramps. Instead, it took the machine about 12 days.

“That wasn’t using any of my time,” he added. “That was just compute time.”

Now, he’s creating computer-based field maps that inspectors with the county’s construction division can use to check every curb ramp and begin prioritizing them for upgrades.

“They can put information in there on the current ADA curb ramp – maybe the date it was installed, the date it was inspected,” Cacioppo said. “They can right there on the spot in field maps delete anything that’s not a curb ramp, and add anything in that is, so that will get cleaned up in [real] time.”

That’s a far cry from the spreadsheets the county used to use to track curb ramps in the 1990s, said Todd Spark, maintenance superintendent at the Omaha Public Works Department. Now, every ramp is an asset in GIS and has an inspection report attached to show when the ramp was built, who built it and if it complies with the ADA.

“I was actually very surprised how many ramps were out there we weren’t aware of,” Spark said. “It was actually shocking compared to what our inventory showed.”

As the county creates a formal ADA compliance transition plan for curb ramps, the tool will be useful across city divisions that handle curb repair and replacement: the asphalt resurfacing program, which builds 800 to 1,200 ramps a year, often in older neighborhoods that aren’t compliant, and the sidewalk division, which responds to resident requests, he added.

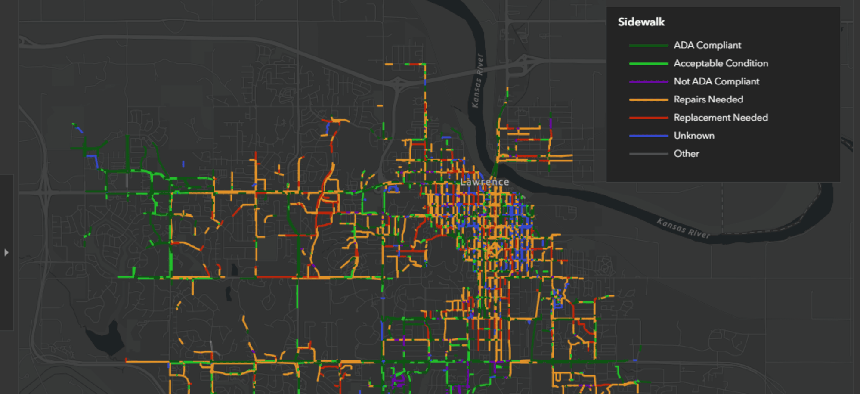

Lawrence, on the other hand, has been working on such a plan for several years. Officials there aim to transition almost 6,600 curb ramps within the next 20 years. That’s based on a study of the city that they did using LiDAR and GIS technology from Esri to model sidewalks to understand areas with high pedestrian demand, low-income neighborhoods and those with zero-vehicle households.

The LiDAR, attached to slow-moving vehicles, captured details to let the GIS team analyze slope and dimensions. With the data, the team created a dashboard that displays information such as curb slope, vegetation obstructions and other factors for all curbs.

“One of the things that we came away with is that about 70% of our sidewalks and about 70% of our curb ramps needed to be addressed either through repair or reconstruction,” said Evan Korynta, the city’s ADA compliance administrator. “It helped us prioritize what areas in town we need to be in first.”

They use a rating system of one through 10, with 10 being the highest priority.

“We look at these Level 9 and Level 10 priority areas, then what we can do is look at the annual funding that we have available each year and pick out an area or a couple blocks that we think we can get done with the money that we have,” he said.

Next, inspectors can go to those areas and note hazards, repair needs, square footage and more.

Previously, “we did more of a complaint-based [response], and it was really spot repair or trip hazards,” Korynta said. “We really wanted to take more of a corridor approach, where we’re actually doing block end to block end so we can actually look at multiple properties all along the stretch and figure out what they need.”

City officials worked closely with the public to ensure support for the transition plan. For instance, they made the map publicly available to help with storytelling about how the curb ramp revamp will help residents overall.

Currently, only static shots are available, but “part of our asset management work is…getting a dashboard that then is public and live back posted up,” said Jessica Mortinger, transportation planning manager at the Lawrence-Douglas County Metropolitan Planning Organization.

“Our hope and dream, I think, in the whole story is really continuing to tell the story about the work that we’ve done in the significant capital investment to show that it's paying off in our community,” she added.