Connecting state and local government leaders

COMMENTARY | At least 28 cities have begun or are planning to partly or fully remove highways that have isolated Black neighborhoods.

The $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill now moving through Congress will bring money to cities for much-needed investments in roads, bridges, public transit networks, water infrastructure, electric power grids, broadband networks and traffic safety.

We believe that more of this money should also fund the dismantling of racist infrastructure.

Many urban highways built in the 1950s and 1960s were deliberately run through neighborhoods occupied by Black families and other people of color, walling these communities off from jobs and opportunity. Although President Joe Biden proposed $20 billion for reconnecting neighborhoods isolated by historical federal highway construction, the bill currently provides only $1 billion for these efforts – enough to help just a few places.

As scholars in urban planning and public policy, we are interested in how urban planning has been used to classify, segregate and compromise people’s opportunities based on race. In our view, more support for highway removal and related improvements in marginalized neighborhoods is essential.

As we see it, this funding represents a down payment on restorative justice: remedying deliberate discriminatory policies that created polluted and transit-poor neighborhoods like West Bellfort in Houston, Westside in San Antonio, and West Oakland, California.

Policies of separation

Many policies have combined over time to isolate urban Black neighborhoods. Racialized rental and sales covenants began appearing in U.S. cities in the early 1900s. They changed cityscapes by restricting certain neighborhoods to whites only, which concentrated Black people in other areas. Racialized zoning, outlawed by the Supreme Court in 1917, was followed by single-family or exclusionary zoning, which restricted residents by socioeconomic class – a proxy for race in the U.S.

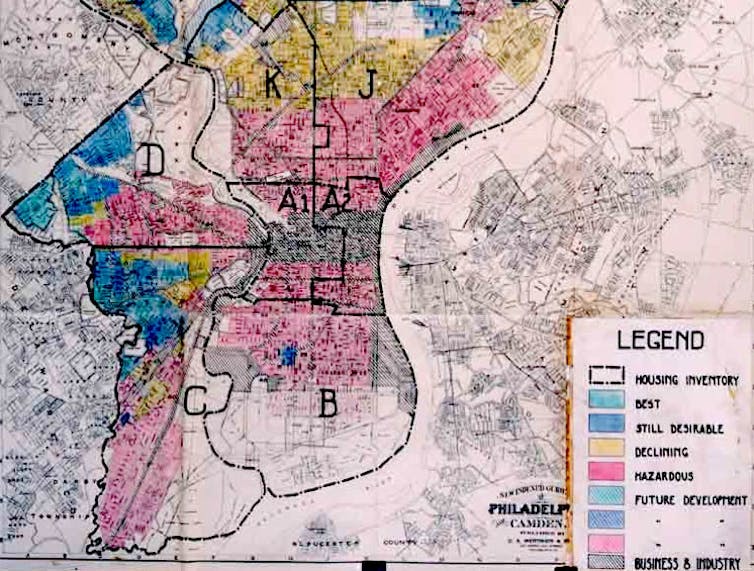

Next came redlining, a classification process that started in 1933 when the federal government rated neighborhoods for its loan programs. Working with real estate agents, the federal Home Owners Loan Corp. created color-coded neighborhood maps to inform decisions by mortgage lenders at the Federal Housing Administration.

Any neighborhood with substantial numbers of Black residents was colored red, for “hazardous” – the riskiest category. Other New Deal programs, such as the Federal Housing Authority and Fannie Mae, built on redlining by requiring racially restrictive covenants before approving mortgages.

Beginning with the first federal highway law in 1956, transportation planners used highways to isolate or destroy Black neighborhoods by cutting them off from adjoining areas. Once the highways were built, the social and economic fabric of these neighborhoods began to deteriorate. Distinguished environmental justice scholar Robert Bullard calls this transportation racism, alluding to the way in which isolation limited employment and other opportunities.

The lasting impacts of highway construction

Today low-income and minority neighborhoods in many U.S. cities have much higher levels of fine particulate air pollution than adjoining areas. Across the U.S., Black and Latino communities are exposed to 56% and 63% more particulate matter, respectively, from cars, trucks and buses than white residents.

Decades of work by environmental justice activists and academics have shown these neighborhoods also are much more likely to be chosen as sites for polluting industrial facilities like incinerators and power plants.

Formerly redlined neighborhoods also have less tree cover and green space today than white neighborhoods. This makes them hotter during heat waves.

One outcome is that life expectancy in the nation’s cities is compromised, varying considerably between the lowest- and highest-income ZIP codes. The worst cities have gaps as high as 30 years.

As one example, Delmar Boulevard in St. Louis is a socioeconomic and racial dividing line. North of Delmar, 99% of residents are Black. South of Delmar, 73% are white. Only 10% of residents to the north have a bachelor’s degree, and people who live in this zone are more likely to have heart disease or cancer. In 2014, these disparities led Harvard University researchers, based on their work on the “Delmar Divide,” to conclude that ZIP code is a better predictor of health than genetic code.

Transportation investments in the U.S. have historically focused on highways at the expense of public transportation. This disparity reduces opportunities for Black, Hispanic and low-income city residents, who are three to six times more likely to use public transit than white residents. Only 31% of federal transit capital funds are spent on bus transit, even though buses represent around 48% of trips.

Reconnecting neighborhoods

Many highways built in the 1950s are now deteriorating. At least 28 cities have begun or are planning to partly or fully remove highways that have isolated Black neighborhoods rather than rebuilding them.

Cities began removing expressways, particularly elevated ones, in the 1970s. While these teardowns were mostly to promote downtown development, more recent projects aimed to reconnect isolated neighborhoods to the rest of the city.

For example, in 2014 Rochester, New York, buried nearly a mile of the Inner Loop East, which served as a moat isolating the city’s downtown. Since then, the city has reconnected streets that were divided by the highway, making the neighborhood whole again.

Walking and biking in the neighborhood have increased by 50% and 60%, respectively. Now developers are building commercial space and 534 new housing units, more than half of which will be considered affordable. The $22 million in public funds that supported the project generated $229 million in economic development.

Other cities that have removed or are removing highways dividing Black neighborhoods include Cincinnati, Chattanooga, Detroit, Houston, Miami, New Orleans and St. Paul. There are only a few well-documented case studies of freeway removal, so it is too early to identify factors leading to success. However, the trend is growing.

In our view, combining highway removal with significant investments to improve bus networks that serve these neighborhoods would significantly improve access to jobs, housing and healthy food. Removing highways would also open up land for new green spaces that can improve air quality and provide cooling. However, we are also mindful that green amenities can cause environmental gentrification in these communities if they are not accompanied by robust support for affordable housing.

Simply removing highways won’t transform historically disadvantaged neighborhoods. But it can be a key element of equitable urban planning, along with housing stabilization and affordability, carefully planned new green spaces and transit improvements. For an administration that has pledged to prioritize racial and environmental justice, removing divisive highways is a good place to start.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Joan Fitzgerald is a professor of public policy and urban affairs at Northeastern University and Julian Agyeman is a professor of urban and environmental policy and planning at Tufts University.

NEXT STORY: Cloud can help speed FOIA response